The girl was eleven years old. She was riding in a group of adults, returning after a long ride down to the creek. They’d just been galloping through corn fields, she bareback on a young Thoroughbred mare, not long off the racetrack; the adults all in saddles. She’d chosen to ride bareback because this large group had used up all of the ‘good’ saddles at the stable. Never mind, she’d done it many times before. The mare had a strong and comfortable back, after all.

As the group passed a sheep barn, the young mare suddenly dropped and shot sideways. Something had caught her eye, though no one could recall what it might have been. The young girl barely registered that it had happened – they simply were eight feet further to the left than they were seconds before. She stroked the mare reassuringly, then continued on as before. “I wish I had a seat like that!” one of the adults said. “I’d have been on the pavement!” said another. The young girl appreciated the compliments, but wasn’t really sure how to take them. She hadn’t done anything, after all. Isn’t that how you’re supposed to sit?

You should sit still and supple. Everything should be stretched, from the head to the hands to the lower leg. Everything should be still, and it should give you the impression that everything is sinking, sinking into the horse, and if you are not careful you are going to break and split in half.

Horses Are Made To Be Horses, Franz Mairinger (Page 60)

That young girl was me. Whenever I read descriptions of a good seat, I think back to that moment when that mare darted sideways, and all the adults marveled that I’d stayed on. I was just a kid on a horse, doing what comes naturally. It happened so fast that I had no time to react – which was probably all to the better. When we react to such moments, our natural response is to tighten our muscles. Such tension is the enemy of the type of seat that Mairinger describes – the type of seat that took me with that mare’s movement. Adults like to say that children are just natural at it, and that it changes as you become an adult. Well …

Twenty years after that little girl was on that trail ride, I was sitting on another mare when a branch scraped the roof of the indoor arena. My mare, who was just coming back from a year off, was suddenly on the other side of the arena in what seemed like just one leap. Just as when I was eleven, the moment happened before I was aware – and just as then, I gave her a pat and we continued on our way. That seat can be gained at any age – for my mother, she learned it in her fifties. It takes work to get it – but the right work, which too often is not what is taught or tried. (Full disclosure, twenty-five years later, after a few serious injuries and seven years of very sporadic riding, that seat has been packed away somewhere. I am in the process of doing the very things I’ll be writing about in order to get it out of ‘storage’.)

The Natural Seat

How did I get that seat in the first place? Well, there is absolutely nothing better than growing up riding your pony bareback across hills and streams. As a young child, you have little fear (as long as your pony is a decent fellow) and you just do what you want to do – nature takes care of the rest as your body learns to balance and assume a position that allows you to follow the pony in all situations. I was not quite that lucky, but I had the next best thing – the first real riding school I attended required a well-rounded education, which included vaulting. Next to that pony in the hills, nothing gives you a following seat and a clear feel of the horse like galloping around with your legs draped around a vaulting horse!

For the beginning rider, the most important teacher of a correct seat must always be the horse. … The old masters put their students on completely trained dressage horses, initially between the pillars, without stirrups or reins. No other instruction was required than to sit down uninhibitedly the way it felt good, to spread the seat bones well, and to let the legs hang down naturally. … Thus prepared, the student was then put on the lunge line, also on a dressage horse and, again without stirrups or reins, he practiced on a moving horse that which he had learned previously in place between the pillars: to softly follow all movements of the horse or, in other words, to be in balance, which is much more the basis for a good and secure seat than the so highly touted firm grip of the legs.

The Gymnasium of the Horse (Steinbrecht), page 2-3 (2011 edition)

I love that quote from Steinbrecht because it aligns with how I learned and how, a decade after my vaulting days, my mentor (a champion vaulter himself) taught all of his Dressage students. Granted, we did not have pillars, and clearly the students in Steinbrecht’s example rode in saddle – but it’s the principle that the rider learns with legs and arms hanging in a natural position. Gravity does the work of securing the position, because a naturally hanging leg – toes pointing down, knees turned slightly out so the leg wraps around the horse – allows the riders hips and seat bones to open and relax. This, above all else, is the requisite of that seat that allowed me to follow those two mares in their dramatic spooks.

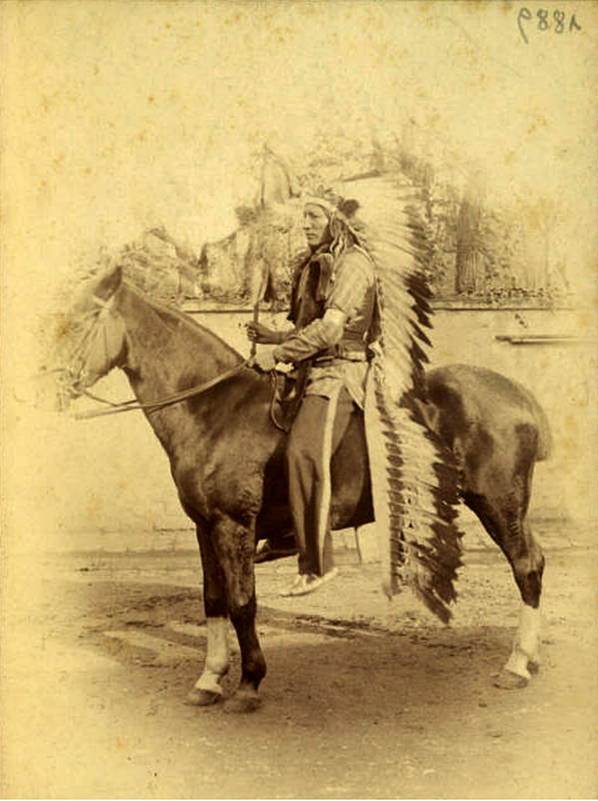

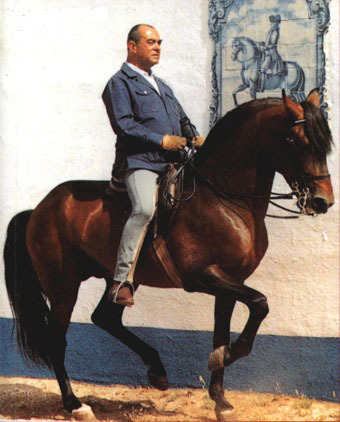

As can be seen in the three images above, this ‘natural’ seat has a long lineage. If you look across history and cultures at images of riders seated without a saddle, or at least stirrups, and you will find that this seat was basically universal. You will sometimes find images of a full gallop, where the knees are brought up in order to support the rider in a raised and forward position, which benefits both horse and rider in that situation. Those children I mentioned, who bang around the hills on their ponies, will develop a seat like those above, all on their own. That it is so ubiquitous, when tack and lessons don’t get in the way, proves that it is the most natural position there is.

In effect, when a rider is forced into a predetermined ‘correct seat’ with no regard for any state of relaxation, he becomes nothing but a puppet, unable to feel or influence.

Riding Logic (Museler), Page 18 (5th Edition)

The challenge in modern riding education is that many trainers start out trying to teach the classical equitation position. In lunge lessons or work without stirrups, instructors focus on keeping the leg in a certain position, back straight, head up, etc. The focus on trying to place your parts gets in the way of the very basic skills you need to ride well – relaxation, feel, and balance. Who hasn’t been in a ‘heads up, heels down!’ type of lesson and felt stiff, bounced around, or had some body part sore because it stayed locked in place too long? How many riders do you see today with stiff elbows and arms, or heels locked down in a rigid leg?

So, if you’re not a child with a pony and hills to roam, or you aren’t about to start your career in vaulting, what are you to do? Fear not! There certainly are things you can do to improve your seat, balance, and (as a result) your posture – but my suggestions will likely require you to leave behind some of the lessons you may have been taught along the way. Provided you have a horse you are comfortable with, you may find some of these suggestions are actually fun. Hopefully you will also find they improve your riding!

A Word About Saddles

Modern saddlers have gone overboard with deep seats, blocks and rolls meant to give you a false sense that you have a secure seat. Until the late 80s saddles had fairly thin and simple flaps, and rather flat open seats. It took skill to sit in these saddles – but they did not get in your way. I found it interesting, a couple of years ago, that a study found flapless saddles increased rider stability. I am hoping that more studies like this may lead to a trend away from all the blocks and rolls. Here is my one simple rule: if your saddle does not allow you to sit with your legs dangling straight down, without interference, pressure, or making your back over-arch, then you have the wrong saddle. If you cannot sit in a natural position in the saddle, you will not succeed in gaining a high functioning seat and position. (More to come on saddle styles and their effect on your seat in a future post.)

About your horse

In order to work on your position, you need to have a safe horse that you trust. Although the work described below builds slowly, it requires that you drop your stirrups. Some horses may react to stirrups hanging at their side, or crossed over their withers, so try working with that through lunging your horse before doing it while mounted. Also, make sure your horse does not have a sensitive back, and you will be changing how you sit and that could disturb a highly sensitive horse.

The Work

Each day that I climb in the saddle, the first thing I do is let my legs hang, working on relaxation and balance. I recommend this for all riders. Here’s how to do it:

- At a halt, hold the reins in one hand on the buckle alone; let that hand rest on the horse’s withers, the other hand hangs straight down from the shoulder

- Drop your stirrups and allow your legs to hang down on your horse’s side; knees should roll slightly away from the saddle, toes dangling down, so you feel gravity holding you in the saddle and your legs wrapping naturally around the horse’s barrel

- Now feel for where the pressure is in the saddle? Tail bone? Seat bones? Crotch? Experiment with adjusting your seat in the saddle (forward or back) and the angle of your pelvis until you begin to feel an even pressure between pubic bones and seat bones

- When you find that balance point, rest there and make sure your legs are still stretching naturally (don’t press anything down, just drape)

- Now check your shoulders and upper arms – are they hanging naturally?

- Maintain this position for a few minutes, increasing the amount of time each day, before picking up your stirrups

- To pick up your stirrups, lift only your toes first (one side at a time), then slowly bend your knee and hip joints until you can just get your foot into your stirrup

- Stand for a moment and try to regain the feeling you just had, only this time the stirrup is simply stopping your leg from hanging straight – but you should still have the feeling that it is hanging

Tip: If you can get a helper, do it! It does not have to be anyone with knowledge of riding. First, your helper can look for things like whether you are sitting forward or back of vertical, whether your legs and arms are truly hanging, etc. But most importantly, for best result have them put your foot back in the stirrup. This allows you to keep your leg hanging, joints loose, while they push up the bottom of your foot until they can slide the stirrup onto your foot.

The example

My mother graciously volunteered to be my model for this. Review these three photos, with details below each.

In this first photo, she has just mounted and walked to the center of the arena. At 80+ and just getting back to riding after a layoff of several months, this is how she naturally sits. Note the rolled forward shoulder, meaning her upper body is tight. The leg looks okay, but the joints are not evenly bent and the ankle is tight.

Here she has dropped her stirrups and is letting her legs hang with gravity doing the work. Her knee is a bit more open than the previous photo, toes also more away from the horse. This has allowed her hips to open more, and has brought her seat just a bit deeper in the saddle. The upper arm is closer to vertical now, with the shoulder much looser.

This is after the stretch. Shoulders now back and more square. Note that the hand is basically in the same position, but the arm is now vertical (the shoulder has lifted slightly – the second photo is better there). The hip, knee, and ankle now have more even bends, making the leg more ‘elastic’. Compare this photo to the classical seat illustration, above, and you can see that line through ear, shoulder, hip, and back of heel.

We did not do any manipulation to my mother’s position in these photos – just allowed her to find that natural seat position. Ideally, as she gets more relaxed and riding fit, the back will come a bit more flat, the shoulder will stay hanging, and the toe will drop even lower without the stirrups, as the hips get more loose. But as you can see, just that few minutes at the beginning can make a big difference in relaxation, balance, and position.

Of note here are her legs. One complaint I hear from a lot of riders is that their knees and toes point away from the horse too much. This is one reason why so many instructors have their students hold the leg in place when working without stirrups – to work on locking the leg closer to the horse. The trouble is, that locks the muscles, tightens the hips, and ends up doing the opposite of what you want.

Look at the different leg positions between the first and last photo of my mother, above. Note that in the first photo her toe is pointed a bit away from the horse. As a result, you can see part of the bottom of the sole of her boot, in the forefoot area. During the stretch, her knee and toe come even further away from the horse; yet, in the final photo her toe points straight ahead! When you allow the hips to open and the muscles to relax through a stretched leg, it actually becomes easier to have your knees and toes pointing straight ahead when you regain your stirrups.

Further Work

As you get more comfortable with this ‘natural’ position, try the following:

- Once you have practiced at the halt, start dropping your stirrups while doing the first part of your walk warm-up. Aside from the points covered for the halt work, start to feel the movement of your horse’s back under your seat. Don’t try to follow it – if you are sitting well draped around your horse following will occur naturally. But feel how the movement affects your seat, and start to feel each step through your seat.

- Once you have added it to your walk warm-up, start to add it to the walk breaks you take during your riding session. This will really begin to reinforce the feeling, as you return to it several times in your sessions.

- Once you get really comfortable, try some exercises with your upper body:

- Reach across your horse’s withers to touch the top of the opposite shoulder; e.g., right hand crosses to touch the top of the left shoulder; gradually see how far down the shoulder you can reach without losing your seat or tightening your legs

- Reach up the top of your horse’s neck and touch his mane; start with a small stretch forward, gradually increasing your reach; try it with each hand

- Reach behind you to touch your horse behind the saddle (as long as he isn’t ticklish back there); gradually increase how far back you reach, alternating hands

- In each of these stretches, always return to your neutral, natural seat position in between

- When you feel ready, try sitting the trot this way. For added security, you can hook one hand into the front of the saddle – but don’t hang on to it, as that will drive tension. Try to just use it as an emergency grip.

- Eventually you will reach a point when you feel comfortable cantering without your stirrups, in the natural position. When you reach that point you truly have accomplished something!

Build up to each of these exercises slowly. You want to challenge yourself, but not scare or injure yourself – or your horse. Pay attention to how your horse is reacting as you try each new thing. Hopefully, as time goes on, you both will become much more comfortable.

I close this important chapter by asking each rider who truly wants to earn this title to let each of his limbs find its resting point, and thus steadiness, by letting it hang under its own weight, and to put no force or stiffness in his overall posture.

The Gymnasium of the Horse (Steinbrecht), page 8 (2011 edition)

Ironically, as I was wrapping up this piece, two friends shared an article from 2015 in which former masters from the Spanish Riding School and Cadre Noir discuss position. You will find some common themes in that article, as well as some additional exercises you can try for different position issues.

In the future I will be writing more about position, addressing each of the areas of the rider’s body, the common faults, and exercises you can do to correct them. But the first thing that all rider’s need, before they can fix their position, is to have a seat!

Categories: horsemanship, riding

At long last researchers are starting to study and document the details of a supple seat!

https://www.horsetalk.co.nz/2020/08/19/sensors-key-differences-advanced-recreational-horse-riders/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting that they picked the Spanish Riding School for the expert riders. Very different from how most professionals ride. Good start, though no surprises. Does fit in with something I’m in the process of writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most professionals do not have anywhere near the influence on their horse as is expected at the Spanish School of Riding. Beyond the relative positions of the horse and rider being correct in the show ring, that is the horse is rarely on top, I do not find a lot to admire in the mainstream horse industry. Of course, poor seats and incoherent aids are probably why they resort to things like electric spurs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is why I am so suspicious of modern studies in riding – things like bit pressure, etc. Too few quality riders to use. Definitely agree with your comments!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read about one study that concluded most professional horsemen rode with up to 60 pounds of pressure per square inch on each rein. That is like riding around with a full sack of feed hanging off each side of the bit. Poor horses!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t that just horrid! 😞

LikeLike

Interesting post. I returned to riding after a too long stretch where work got in the way. 9 years years ago I finally retired and decided to get back on a horse. I decided, too, that since it’d been years since I’d been on a horse, and I’d never had a formal lesson, I would go back to kindergarten riding school. I started riding bareback. In fact, for the first several weeks, I had a friend lead the horse as I sat on his back with my eyes closed and my hands behind my back. Nothing helps you find your balance better than riding eyes closed!! Of course, you have to have someone who knows how to lead a horse and how to read the horse…

Riding bareback improved my seat tremendously. Learning to balance without hanging on the reins gave me a ‘soft hand’. But it did come with one problem…I don’t want to ride in a saddle. At all. I much prefer bareback. Which means no dressage shows…but that’s okay. I will always prefer bareback. An added bonus is there is minimal tack involved…no saddle to clean!

I advise anyone that, if htey want to develop a good solid independent seat…go bareback.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds like you took a smart – and brave – approach! Yes, having a skilled and trusted helper is important … along with having a horse whose back is comfortable to sit on! 😉

LikeLike